ART OF THE JOINTS

- Characteristics

- Apprenticeship of the profession

- Raw materials

- Dyes

- Joints

- Shearing and seaming

- Jointing

- Shearing

- Washing

Characteristics

The wonder of the birth of a Persian tapestry comes to fruition at the moment when millions of multi-coloured threads are patiently woven together to form designs, geometric or floral motifs, which bear witness to a sparkling imagination, an ongoing sense of creativity, and an ever-sure taste.

Eastern tapestry therefore is characterised by the fact that it is woven entirely by hand.

Handknotted rugs has the following components:

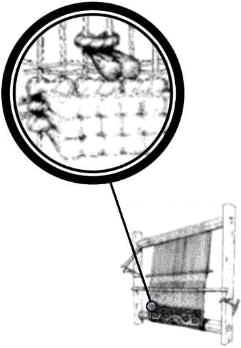

Traditional tapestries are woven on a horizontal or vertical loom. In both cases the loom consists of a frame upon which the threads are tightened to form the casing of the tapestry.

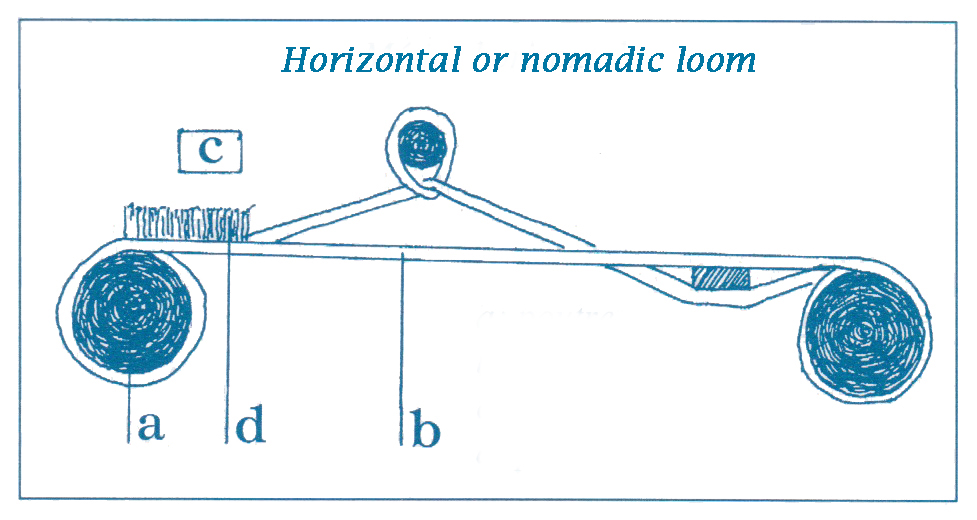

The horizontal or nomadic loom (level surface): this loom is located just above the ground and consists of two wooden parallel beams (cylinders) supported at the edges by stakes thrust into the ground. Nomadic tribes this kind of loom which can easily be dismantled. The weaver is seated on the part already woven and he advances according to the progress of his work.

|

a: beam b: warp c: the weaver place d: strand of wool make the carpet pile e: rolled up warp |

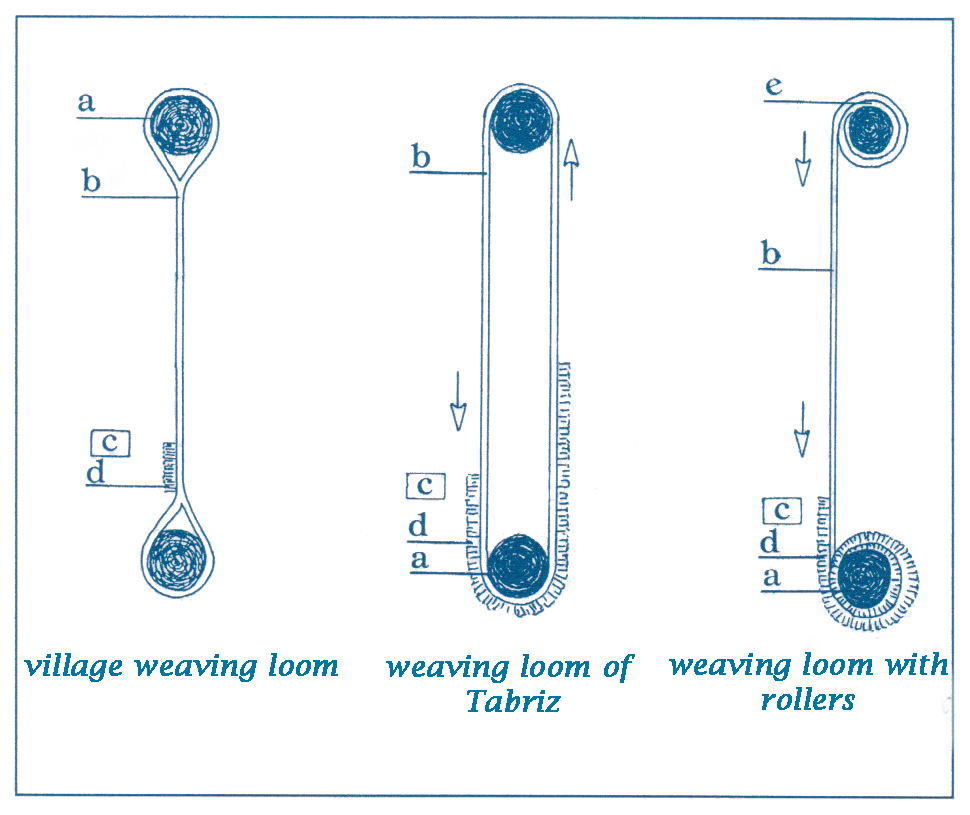

The vertical or village loom (vertical surface): on this loom the threads are laid around the two threads which are supported by two vertical beams. With this type of loom the weavers must elevate their seats as the tapestry progresses. There is another type of loom to solve this problem: the vertical loom fitted underneath with a moveable roller. In this case the tapestry is rolled up little by little on the cylinder underneath. There is also a third type of vertical loom with rotating wheels and a braking system. The threads are rolled up on the uppermost roller and, when the tapestry is too high, the weaver releases the system so that his work is automatically rolled up on the roller underneath. This is the loom which is used for very long tapestries.

|

a: beam b: warp c: the weaver place d: strand of wool make the carpet pile e: rolled up warp |

Apprenticeship of the profession

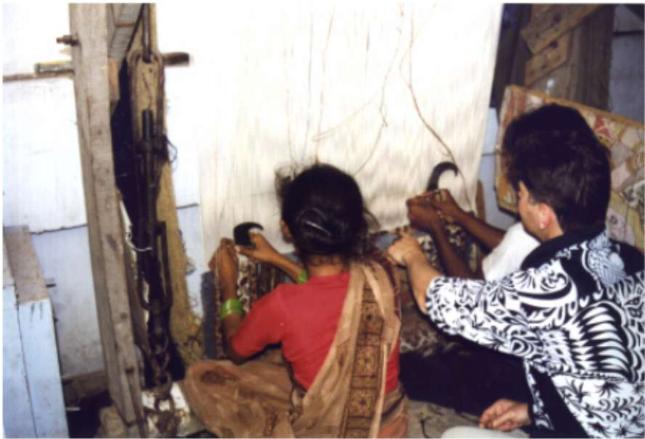

For as long as we can remember Asian women have always weaved tapestries at home. Such little girls have a certain handiness so that they can easily learn the technique. In general, they work first of all on a miniature loom. As soon as they have mastered the technique, they work together with their mothers, their grandmothers, or other family members who teach them other designs. By the age of ten they usually have mastered the technique completely, but, of course, tapestry weaving involves more than just weaving. They also have to learn other skills such as sorting the wool, unravelling, twining, setting the threads on the loom, and cutting the tapestry. As soon as they have mastered all this they can then make an entire tapestry without having to leave the house.

The basic techniques which are used by nomadic weavers are the same as those used by those who work at home. The biggest difference is found in the loom. The nomads use a horizontal loom, whilst domestic weavers and village workers use a vertical loom.

Raw materials

The materials necessary for making an eastern tapestry are wool, silk, and cotton.

The materials necessary for making an eastern tapestry are wool, silk, and cotton.

Wool and silk are used mainly for the tapestry pile and rarely for the warps and threads for which cotton is used most often. Sheep's wool is generally preferred, although nomadic tribes occasionally use goat's or camel's wool.

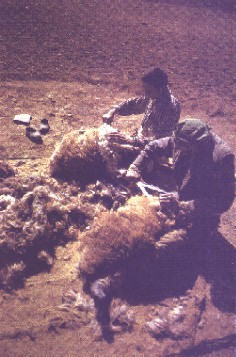

The quality of the wool varies according to the various parts of the fleece. The wool is sorted by hand into several piles according to its quality and this task requires skill and experience. The quality depends largely upon the length and firmness of the threads. The climate, pasture, age of the animals, shearing season, and the sheared fleece are all important factors which help to determine the quality. Lower quality wool from both summer and winter is used for felt.

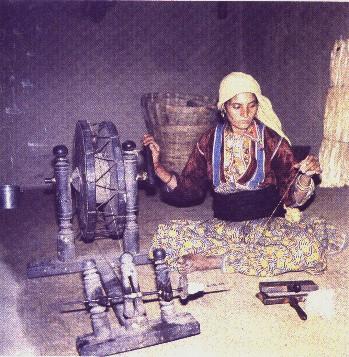

Manual spinning-wheels are found all over Asia. This Indian woman is using a beautiful model for spinning the combed wool (the combing tools and the mass of wool are on the ground in front of her).

Manual spinning-wheels are found all over Asia. This Indian woman is using a beautiful model for spinning the combed wool (the combing tools and the mass of wool are on the ground in front of her).

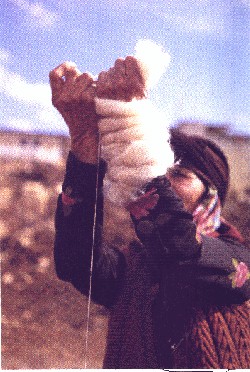

Spinning the wool. The skeins of wool are rolled around the wrist of the weaver who uses the other hand to produce a regular thread while the spool turns.

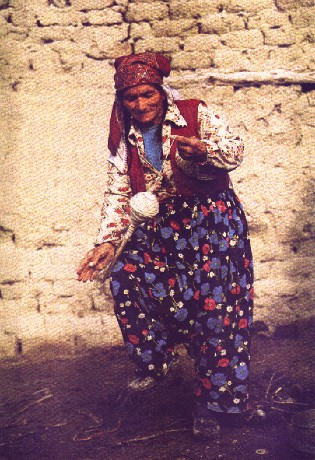

This woman is twisting some wool using a spindle. In order to do this she spins the equipment in the opposite direction putting the spindle over her thigh. Most of the time this work is done using a spinning-wheel.

This woman is twisting some wool using a spindle. In order to do this she spins the equipment in the opposite direction putting the spindle over her thigh. Most of the time this work is done using a spinning-wheel.

Dyes

Vegetable dies

Persian tapestries are renowned for their wonderful range of colours. Originally, all the colours were made from natural animal or vegetable substances or even from insects. Painting is a very delicate operation which takes quite some time. The material to be painted is first of all placed in a bath of concentrated alum which acts as a staining agent. The dyes which are most used are the following:

Persian tapestries are renowned for their wonderful range of colours. Originally, all the colours were made from natural animal or vegetable substances or even from insects. Painting is a very delicate operation which takes quite some time. The material to be painted is first of all placed in a bath of concentrated alum which acts as a staining agent. The dyes which are most used are the following:

- the red which originates from madder-roots and which grows in the wild in large parts of Persia from insects like cochineal or certain desert flowers;

- the yellow which is obtained from yellow weed, wine leaves, the skin of pomegranates, and saffron. The very dark, almost black, streaks were obtained from indigo crusts which form on the walls of the tub in which the dyes are left to ferment;

- the brown is obtained from nutshells or from the bark of an oak tree and onion skins;

- the green is obtained from a mixture of yellow and blue with copper sulphate.

The natural colours of the wool ensure the grey and chestnut which can equally be obtained from walnut stains.

In spite of the fact that the three base colours (red, blue, and yellow) exist separately, it is not possible to obtain all combinations of colours because many of the natural dyes do not mix well with each other by reason of the great diversity in the base material.

Colouring with the use of natural colours therefore largely depends upon the knowledge and skill of the workers, but equally the mordant and the composition and hardness of the water influence the colouring.

Persian tapestries often appear, at first sight, to be strangely characterised by a light and sometimes obvious colour difference: the colour of certain designs or the variation from one spot to the other seems to make an enormous difference. This modification of colours, called abrash, is found mainly in the ancient tapestries. The presence of abrash proves that the tapestry has been coloured using vegetable colouring. In fact, it is very difficult when using vegetable substances to reproduce the very same colour twice.

Persian tapestries often appear, at first sight, to be strangely characterised by a light and sometimes obvious colour difference: the colour of certain designs or the variation from one spot to the other seems to make an enormous difference. This modification of colours, called abrash, is found mainly in the ancient tapestries. The presence of abrash proves that the tapestry has been coloured using vegetable colouring. In fact, it is very difficult when using vegetable substances to reproduce the very same colour twice.

Synthetic dyes

Working with vegetable dyes is a long and delicate process. We understand, therefore, why modern workers search for quicker methods which are better suited to the needs of business.

The first synthetic dyes appeared around the middle of the 19th century. They were discovered in England by William Henry Perkin. Aniline is a dye extracted from coal tar (obtained by the destructive distillation of organic matter such as wood, turf, and coal) which is used to colour the wool. Aniline base dyes were quickly imported to Turkey and Persia around 1870. In spite of their great success, low price, and brilliant shine aniline base dyes are very inconsistent; they lose their shine and decay rapidly (yellow becomes a shade of green-brown, red becomes purple, and blue becomes grey-brown). Nowadays, aniline base dyes are no longer used for colouring the wool.

The most widely used dyes for colouring the wool are the chrome pigments first used in Europe in the 1920s. They have outstanding qualities: they are more consistent than most natural dyes, they do not become discoloured, they are light resistant, and they do not affect the wool. They are generally used in all countries where tapestries are made.

Nevertheless they were abandoned around 1990 for the benefit of acids or metal dyes.

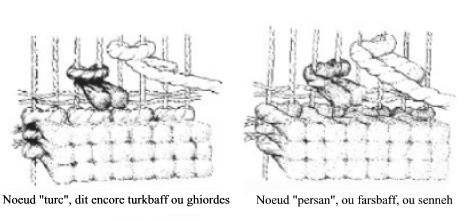

Joints

There are two distinct sorts of joint: the ghiordes or turkbaff, and the senneh or farsbaff. It is strictly more correct to to use the names the turkbaff and the farsbaff which indicate the regions where this type of joint is most frequently used.

In fact, the turkbaff, or Turkish joint (symmetrical joint), is used essentially in Turkey and in The Caucasus whilst the farsbaff or Persian joint (asymmetrical joint) is used mainly in Persia. Besides, it is a remarkable fact that in the small town of Senneh (or Sanandaj), after which the Persian joint is named, the tapestries are woven with a Turkish joint.

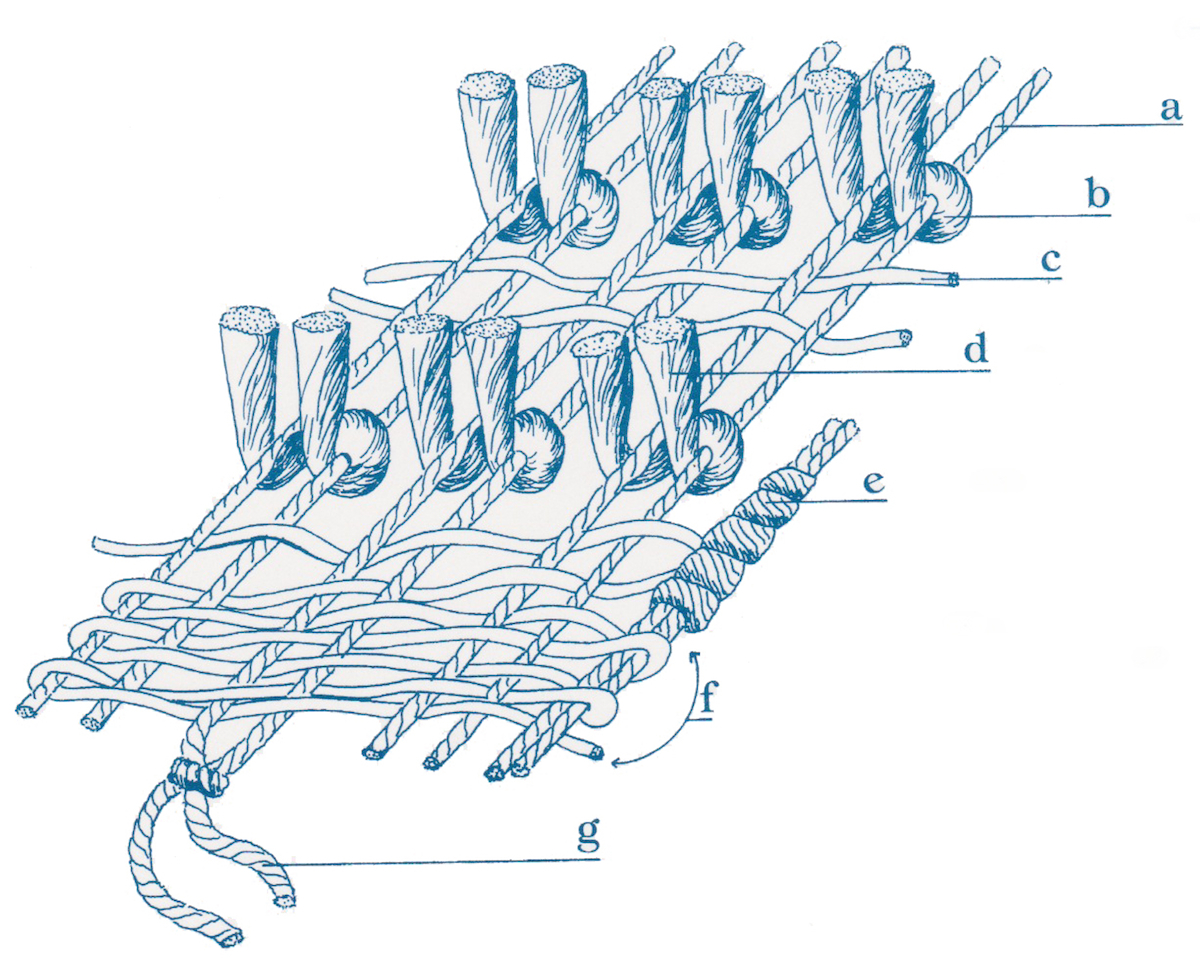

In the Turkish joint, the thread of wool is rolled around the two warps so that the ends stick out between the two warps.

In the Persian joint the thread forms a single spiral around one of the two warps in such a way that at the side of each warp one of the ends of the wool threads sticks out (pile). The Turkish joint is somewhat stiffer than the Persian joint which, in turn, is more suitable for stiffer warping and weaving.

In order to know which of the two joints, Turkish or Persian, has been used we remove the tapestry pile so that a row of joints becomes visible.

In the turkbaff the two ends of thread stick out from the mouth of the joint, whilst in the farsbaff only one end sticks out and the other can be seen alongside it.

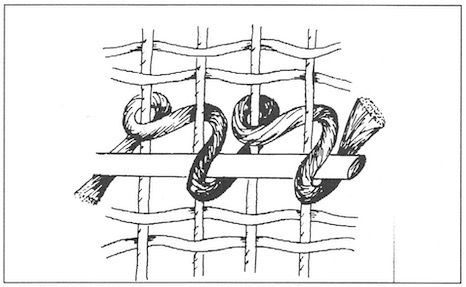

The Tibetan knot is only used in Tibet, Nepal and western China. A metal rod is placed in front of the warp and the strands of the carpet are tied around this rod which thus determines the height of the pile. The velvet threads are then cut.

Shearing and seaming

The vertical threads which are stretched out between the two ends of the loom are called the shearing (or warps). The pile joints are placed around it. The warps are usually cotton. However, on nomadic tapestries the warps are wool and sometimes they are even silk if the tapestries are pure silk.

The vertical threads which are stretched out between the two ends of the loom are called the shearing (or warps). The pile joints are placed around it. The warps are usually cotton. However, on nomadic tapestries the warps are wool and sometimes they are even silk if the tapestries are pure silk.

The tapestry edges are actually the ends of the warps. The woof is formed by one or more diagonal threads. In general, there are two (one loose and one tight thread) which are woven between two rows of joints. As with the warps, the woofs can be cotton, wool, or silk. The woofs strengthen the parallel rows of joints and give the tapestry a certain stiffness. For this reason the woofs are pressed down against the row of joints by the use of a special comb.

- The warp, usually cotton, consists of vertical parallel threads which are stretched out along both sides of the frame.

- The woof consists of one or several cross-stitches, almost always cotton, which are woven between each row of threads.

- The pile is the uppermost surface of the tapestry: it is usually made of wool and is formed from short threads which are woven around the warp. The threads are placed in rows all over the breadth of the tapestry, but never in the height.

Jointing

First of all an edge is woven onto the underside of the tapestry. The weaver runs a number of woofs through the tight vertical warps until the edge is stiff (kilim tissue). This ensures the stiffness of the tapestry and prevents the joints from coming loose.

As soon as the edge is ready the actual weaving can begin. The woollen threads are wound around the warps whereby the pile comes into being. The joints (turkbaff or farsbaff) are continually laid around two warps all across the width of the tapestry. After the joint has been made, the weaver cuts the woollen thread off about 4cm from the joint and shuts the ends by pulling downwards and pulls the joint thereby determining the direction of the tapestry pile. A Persian tapestry always has a lighter and a darker side depending upon the direction of view and the incidence of light on the pile.

As soon as the edge is ready the actual weaving can begin. The woollen threads are wound around the warps whereby the pile comes into being. The joints (turkbaff or farsbaff) are continually laid around two warps all across the width of the tapestry. After the joint has been made, the weaver cuts the woollen thread off about 4cm from the joint and shuts the ends by pulling downwards and pulls the joint thereby determining the direction of the tapestry pile. A Persian tapestry always has a lighter and a darker side depending upon the direction of view and the incidence of light on the pile.

When a row of joints is ready, a seam is woven alternately above and beneath the warps.

After the seam has been done, the row of joints is one again pulled tight before the weaver begins the following row of joints. The pile is sheared for the first time every 4 to 6 row of joints (sometimes even after every row). The ends are cut off consistently at the same length.

It is self explanatory that the price of a tapestry depends upon the time taken for the weaving or, in other words, the tightness of the joint. Making the joints is done at a rapid speed. An experienced weaver can make, on average, about eight thousand joints per day. That is quite a lot and yet even this represents only a small part of the tapestry surface. At a speed of ten thousand joints per day (this is the maximum) the worker needs five months to complete a two metres by three tapestry of average quality of 2500 joints per square decimetre. After a full day of work without a break, weaving proceeds over only 2cm of the entire width. With a joint tightness of only 500 joints per square decimetre a tapestry requires only one month's work.

It is self explanatory that the price of a tapestry depends upon the time taken for the weaving or, in other words, the tightness of the joint. Making the joints is done at a rapid speed. An experienced weaver can make, on average, about eight thousand joints per day. That is quite a lot and yet even this represents only a small part of the tapestry surface. At a speed of ten thousand joints per day (this is the maximum) the worker needs five months to complete a two metres by three tapestry of average quality of 2500 joints per square decimetre. After a full day of work without a break, weaving proceeds over only 2cm of the entire width. With a joint tightness of only 500 joints per square decimetre a tapestry requires only one month's work.

To do full justice to a Persian tapestry it is important that both directions are tried out until one has the desired incidence of light.

The nomadic weaver does not use a colour or draft design. He is led by instinct or tradition. He starts with a general idea whereby he takes into account the desired format, the symbols which he wants to include in it, and the colours at his disposal.

The rest is left to his imagination, skill, and creativity.

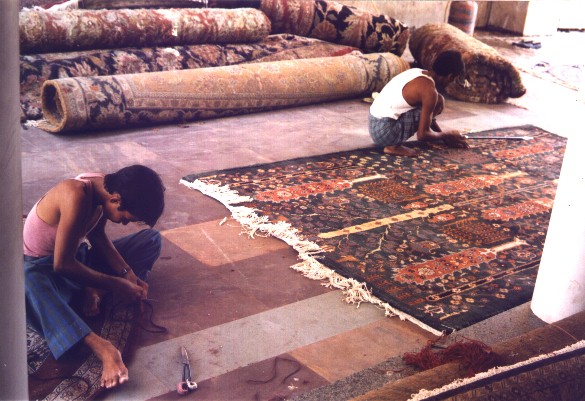

Workers in family or urban studios base their work around a plan. The draft is transferred to a check carton whereby every corner represents a joint. If the weaver works alone, he puts the carton in front of him on the loom. However, if several weavers work together, one of them has the job of reading aloud the number of joints. When we visit a Persian village we often hear coming from the houses the following constant litany: "One red joint, two blue joints, three red joints". This is the voice of the head of the family who is working together with his son on the same tapestry and they are each claiming half for their accounts. Joint by joint the tapestry gradually takes shape. In studios with a lot of staff the work is led by the ustad (master) who reads aloud the written instructions. He directs production and takes part himself in delicate operations.

Workers in family or urban studios base their work around a plan. The draft is transferred to a check carton whereby every corner represents a joint. If the weaver works alone, he puts the carton in front of him on the loom. However, if several weavers work together, one of them has the job of reading aloud the number of joints. When we visit a Persian village we often hear coming from the houses the following constant litany: "One red joint, two blue joints, three red joints". This is the voice of the head of the family who is working together with his son on the same tapestry and they are each claiming half for their accounts. Joint by joint the tapestry gradually takes shape. In studios with a lot of staff the work is led by the ustad (master) who reads aloud the written instructions. He directs production and takes part himself in delicate operations.

The tapestry finishes exactly as it started, namely with an edge. After the last row of joints more seams are threaded through the warps whereby the tapestry is stiffened. The warps which stick out along both sides are either rolled up or tied into fringes. As soon as the tapestry is fetched from the loom, it is sheared for the last time and then washed.

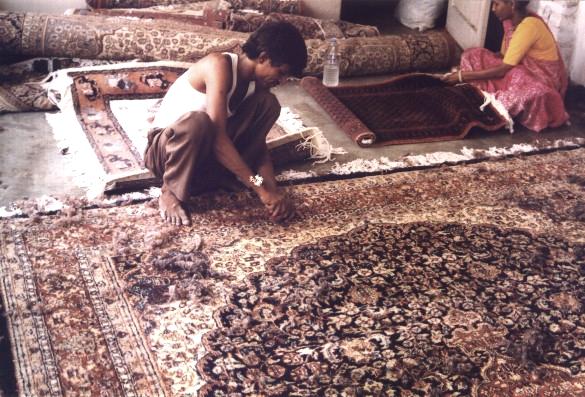

Shearing

It is only when the tapestry is completed that the pile is finally sheared. This is a delicate operation which gives the tapestry its final shape and is always done by a specialist. If the tapestry is very thin, the strands are cut very short; by contrast, the pile is much longer in cases where the tapestry threads are less tight because otherwise there is a risk that the weak structure of the tapestry will be visible.

The height of the pile also depends upon local custom or market demand. The nomads, for example, tend to prefer a very high pile, whilst urban artisans cut the pile very short, and then there is also the American market which currently exerts a strong influence upon Persian production and mainly requires tapestries with a pile of medium height.

Washing

Washing the tapestry restores its vigour and softness and the colours are restored to their original freshness. The tapestry is then laid out in the sun to dry and this allows the colours to be tested for one last time.

After the pile is dry it is combed between each row of threads in the extended section warp. This is achieved with the help of a conical tool with four sides.